Sense of Hearing

- HOME

- STORY

- TOKYO WAVES magazine

- Vol2 sense of hearing

Edo Wind Chimes: The Gentle Sounds of Edo Reach the Ears

Sense of Hearing

SHINOHARA FURIN HONPO

SHINOHARA FURIN HONPO

How many of you have furin (wind chimes) at home? In summer, the sound of wind chimes swinging gently in the breeze, under the eaves or near a window, unobtrusively reaches our ears and resonates pleasantly in our hearts. The sound of wind chimes brings a bit of cool relief to the hot and humid Japanese summer. Being able to sense this coolness through my ears was a small wonder that piqued my curiosity. With the widespread use of air conditioners, few people today may hang wind chimes in their homes, but I learned there are still wind chimes being made according to old traditions. One of those is produced only in Tokyo—the treasured Edo Furin (Edo wind chimes). I looked into their appeal to find out what sets them apart from ordinary wind chimes.

Wind chimes originally came to Japan from China and were known at the time as futaku (wind bells). They developed into a tool to ward off evil spirits and protect against disease and negative vibes. During the Heian and Kamakura periods, nobles began hanging them from the eaves to ward off evil, and it is said that this is when they began to be known as furin. While they had typically been made of metal or ceramic, the Edo period saw the first appearance of wind chimes made of glass. This was about when the first Edo Furin were created. Emi Shinohara runs Shinohara Furin Honpo, one of just two such studios in Tokyo, located in a quiet residential neighborhood in Edogawa-ku, Tokyo. She told me that “These wind chimes are named Edo Furin because they are made in Tokyo, which was once known as Edo, and they continued to be made according to the same methods used during the Edo period” The brand name Edo Furin emerged during the time of the second-generation owner, Yoshiharu Shinohara. Even today, only one clan, approved by Yoshiharu, continues to maintain the production methods used in Edo Period. As just about everything around us is modernizing, it is surprising to hear that they have preserved those methods that go all the way back to the Edo period.

Edo wind chimes have three distinct features. First, the glass is hand-blown rather than molded. Most typical glass wind chimes are mass-produced by pouring glass into molds, but each Edo wind chime is formed by hand, and no two are alike. To start, a small ball, or kuchidama, of molten glass that has been heated in a 1,320°C kiln is taken up on a tomozao (blowpipe), a long glass tube. This kuchidama will later be cut off to form the sound hole. To achieve an even thickness, the blowpipe is rotated over and over in the fingers as the glassblower breathes into it to gradually inflate the glass. Once this piece reaches about the size of a 500 yen coin, the glass that will form the body of the wind chime is taken up from the kiln, and the process of inflating the glass is repeated. Many of you may have seen this on TV or elsewhere, and it is truly a battle against heat and time. Nervously, I decided to try it for myself. The craftsman held the blowpipe for me as I breathed into the tube… but nothing. I tried breathing a little harder. The glass bulged out in a strange shape and then, heartlessly, cracked in two. As I stood there astonished, the glassblower laughed and said, “It’s not something you can learn overnight—your body just has to get used to it.” In front of my eyes, he blew a new piece of glass beautifully. Before the glass cooled, he used a wire to open a hole at one end for the string to hang the wind chime, finally inflating the glass again and forming the final shape with one breath. This series of steps took only a minute or two to complete. As I looked on, in no time he had made a beautiful, transparent wind chime. A piece of true craftsmanship!

The second feature of Edo wind chimes is the serrated edge of the sound hole. The wind chime is cut from the blowpipe at the bottom using a whetstone, but the edge is purposely left rough. When you think about it, the sound hole on a typical glass wind chime has a smooth edge. It was fascinating to learn why they leave it rough—it is intended to produce the distinctive sound of the Edo wind chime. It is designed so that the chime itself, a piece of glass pipe, brushes against the sound hole and produces a sound as it swings in the wind. I always thought it was the sound of the chime hitting against the sound hole; I did not realize the sound was produced by it brushing against the edge. Ms. Shinohara notes that “Since the size and thickness of each wind chime is different, they produce a variety of tones. The sound varies by material as well—the sound of an iron wind chime will linger, but Edo wind chimes do not produce a lingering sound. It’s softer, but more refreshing.” As she spoke, behind her the cool sound of the Edo wind chimes, swinging in the breeze, each rang out in a different way. As I listened more carefully, I noticed that indeed, each was playing its own distinct note—some tinkling gently, others with more of a clanging sound. None of them lingered for long, however, the sound of each fading completely away. Each has its own unique music.

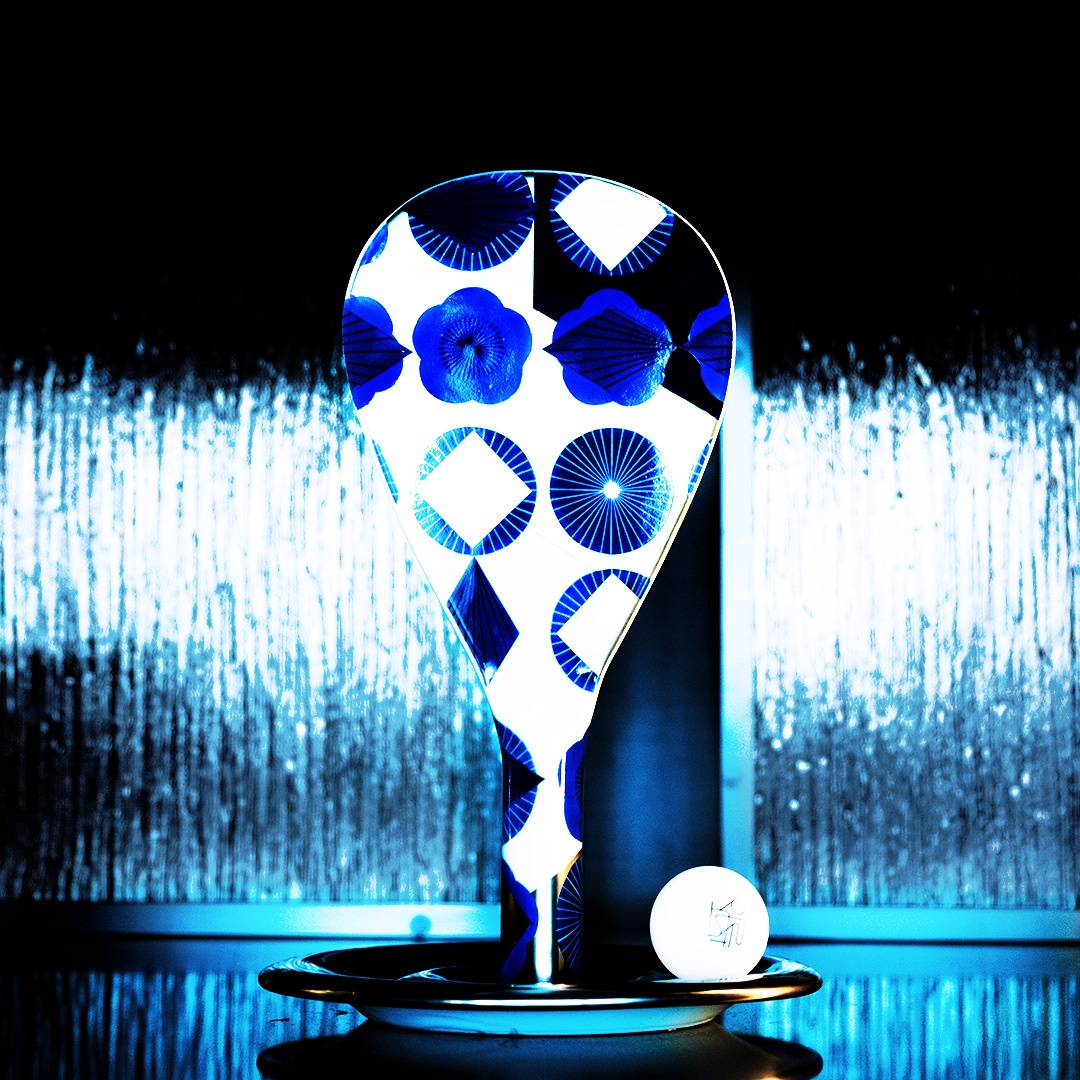

Finally, the third feature of these wind chimes is the way they are painted. “Each is individually hand-painted—from the inside,” says Ms. Shinohara as she carefully ran her brush along the inside of a wind chime. Wind chimes are normally hung outdoors, where they are exposed to the elements. They are painted on the inside to keep the designs from coming off in the wind and rain. I was surprised that so much care was taken in their creation. “Since we use oil paints, they take a while to dry, so we paint one color, wait for it to dry, then add another color, repeating this process until we’re done,” says Ms. Shinohara. It can take two to three days to complete even a simple design. There are a wide variety of designs, too, with popular ones including not only traditional patterns in vermillion meant to ward off evil, but more current designs with morning glories, goldfish, and other cool motifs that symbolize summer. The wind chimes, carefully painted by craftspeople, are lustrous with the shine of glass.

The process of making Edo wind chimes was both delicate and painstaking. Each lovely wind chime is carefully crafted by artisans who bring passion and sincerity to their work, ensuring each will produce its own unique tone. I think it is thanks to the feeling these people have for their work that the music of these Edo wind chimes resonates so gently and pleasantly in our ears. Edo wind chimes taught me that a person’s feelings can reach our ears in this way. I plan to hang one of these Edo wind chimes in my window at home. As I listen to the soothing sounds of Edo on a hot summer day, they are sure to help me relax and make my heart feel cooler—and lighter.

- Information -

Shinohara Furin Honpo

Address : 4-22-5 Minami-Shinozaki-machi, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo

Tel : +81 3-3670-2512

Hours : 9 a.m. – 6 p.m. (Irregular store holidays)

Tel : +81 3-3670-2512

Hours : 9 a.m. – 6 p.m. (Irregular store holidays)

- Interviewer -

Kanako Sato, Marketing Communications, Specialist